The True World War II Story of the Recovery of 8 Tons of British Gold from a German Minefield

PART 2: Trapped in a Minefield

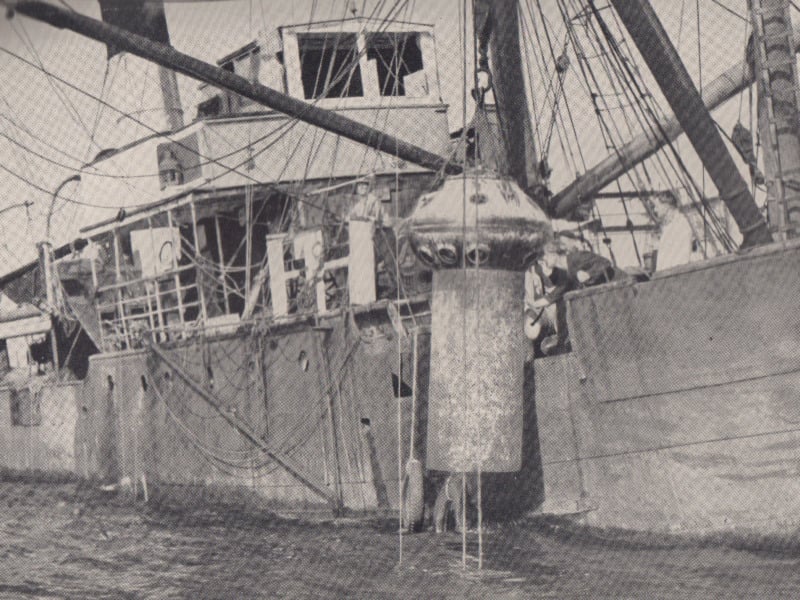

Captain John Williams arrived in the New Zealand town of Whangarei on 20 November 1940. He had with him a crew of ten men from Australia, the underwater observation chamber (which had not yet been put in the water) and the salvage vessel Claymore, the rusting hulk that he had refloated from the mud in Auckland Harbour. The two divers, who were to go down in the observation chamber, were brothers John and Bill Johnstone.

In Whangarei, most of the crew decided they would sleep on the Claymore, and Bill Johnstone recalled how he put a sheet of corrugated iron above his bunk, to stop the water dripping through the deck above, and keep him dry. Other crew members explained that water would often slosh through the cabins, but they soon made friends with the towns people, and when the Claymore was ashore they would be invited to their homes for hot meals and dry beds.

After he arrived in Whangarei, Williams was instructed by the Royal New Zealand Navy, not to attempt to locate the RMS Niagara, because the area had not yet been swept for German mines. It was not known how many mines the German raider had left in the Hauraki Gulf, or the extent of the minefield. Williams waited impatiently at Whangarei for three weeks before a RNZN minesweeper arrived from Auckland, and swept a track about half a mile wide, from the Whangarei Heads to the area where the Niagara was believed to have sunk. Williams now received permission to commence the search.

Williams tried using an echo-sounder to locate the Niagara, but the results were disappointing. The crew continually obtained different depth readings, even when they were passing over the same area. At other times the uneven seabed made it almost impossible to distinguish between a sunken ship and natural underwater formations. Williams decided the only way to locate the Niagara, would be by dragging a small hook along the sea bed. So that was what he did.

At first, the crew dragged the hook behind the old Claymore, sweeping back and forth across the area cleared by the RNZN. But no wreck was found. Williams had no choice but to widen the area of the search. Before he did that however, he wanted to test the underwater observation chamber, which had still not been put in the water. Following a few days in Whangarei, to get fuel, water and supplies, the Claymore put to sea early on 29 December 1940. Once clear of Whangarei Heads, and in deep water, the Claymore was anchored and diver John Johnstone got into the chamber. The lid was bolted down. The chamber was hooked to the winch, lifted out of the forward hold, and lowered into the water.

Johnstone recorded notes in the small logbook that he carried. The chamber slipped underwater at 11.42 a.m. Thirteen minutes later he recorded he had reached a softy muddy seabed. The depth was 370 feet (113 metres).

Via the telephone to the surface, Johnstone instructed Williams to leave the chamber on the sea bed while he checked everything was working as it should. There were no visible leaks, and no increase in barometric pressure indicating a potential leak. The oxygen was flowing steadily from the oxygen bottles. Johnstone was breathing into the face mask so that his exhaled air passed through canisters of soda lime, and his carbon dioxide was absorbed. He did notice that he had to remove the face mask to be able to speak to Williams on the telephone. After 23 minutes sitting on the seabed, Johnstone decided it was time to return to the surface. Above, the crew started to wind the winch in, and raise the chamber. It gently left the bottom and Johnstone, looking out a four-inch (10 cm) porthole watched as the seabed disappeared from his view. As he ascended, he wrote the depth in his notebook.

Suddenly, at 180 feet (55 metres) he was surprised to see a wire rope swaying outside one of the portholes. Johnstone called to Williams to slow the ascent, and asked if the Claymore had any wires hanging over the side. Williams replied that there were not.

Next, Johnstone was alarmed to hear a loud scraping on the side of the observation chamber and called to Williams to stop raising it. Again, Johnstone asked if there were any wires hanging over the side of the Claymore, and again Williams said there wasn’t. Now the wire was right outside the porthole and Johnstone could see it clearly. He studied it, and noticed that the edges of the wire were serrated, like a hacksaw blade. Then he remembered reading that the edges of the wire of German mines were serrated to cut through the thin wire of minesweepers. By telephone he told Williams what he could see.

It was the first time the underwater observation chamber had been put in the water, and it had already managed to wrap itself around a German mine.

The pair discussed their predicament. The observation chamber was hanging on a cable from the surface. The mine was floating, suspended on a cable from the seabed. And, both men knew the German mines that had washed only had their deadly horns at the top, where they could make contact with passing ships. The horns to detonate the mines were not under them, and Johnstone and the chamber were coming up under a mine. Williams and Johnstone decided the only thing to do was to continue lifting the chamber, and hope it would simply push the mine out of the way.

Johnstone recalled it was agony, being raised slowly and listening to the amplified sound of the mine wire scraping on the side of the chamber. Eventually, he heard the thud as the top of the chamber struck the underside of the mine. Then he saw the dark shape sway away and disappear below him. The observation chamber was lifted clear of the water, dropped back into the hold of the Claymore, the lid was unbolted and Johnstone was lifted out, sweating and shaking.

But their problems with that particular German mine were not over. The Claymore had been anchored when the observation chamber was being tested. With the chamber safely back on board, Williams ordered the anchor to be raised. When it was near the surface, the crew saw a large round object, covered with weeds and growth, tangled in the anchor rope. The mine was not going away in a hurry. Because Williams didn’t want to lose a good anchor, Bill Johnstone got into his hard hat diving suit, went over the side, and tried to untangle the mine from the anchor cable. But underwater, Bill Johnstone found the task impossible. At one point, when the current turned, he found himself grabbing the horns of the mine as it surged to the surface, and he was momentarily trapped him between the mine and hull of the Claymore. When he finally wriggled free, Bill Johnstone got out of the water.

The crew hooked a buoy to the anchor chain, released the chain from the Claymore, and steamed back to Whangarei, so they could think about how to proceed. A week later, the Claymore returned to the tangled anchor and mine, this time accompanied by a RNZN minesweeper. The navy fired at the mine and exploded it. Williams had no choice but to buy another anchor.

During January 1941, Williams and the Claymore crew returned to the task of dragging a hook across the seabed in an attempt to locate wreck of the Niagara. On two further occasions they hooked mines and stood off, then waited for the navy to come and sink them.

The search area that had been designated by the RNZN had been marked with buoys. On 31 January 1941, the Claymore hooked one of the buoys with the line they had been dragging. It took the crew about two hours to untangle it and, while they did, the Claymore drifted south, out of the search area. Williams recalled that by the time the buoy was finally untangled, they had drifted so far south that were unsure exactly where they were. He instructed one of the crew to steer the ship north, back to the search area, then he went below deck to get a cup of tea.

As Williams sat drinking his tea, suddenly the trawl winch screamed a sharp metallic scream and the trawl wire pulled tight. They had hooked something large. The crew lowered a lead weight with tallow to the object on the sea bed and when it was raised, paint flakes were stuck to the tallow.

The RMS Niagara had been found.

With the Claymore moored over the wreck, John Johnstone went down in the observation chamber and inspected the Niagara. He reported it was laying with its starboard side up, which was fortunate, because the bullion room containing the gold was on the starboard side.

Once the exact position of the Niagara, was established, six massive concrete mooring blocks were placed on the seabed around the wreck, with cables to the surface and mooring buoys. The Claymore would steam into the middle of the mooring buoys and, using the longboat, the crew would hook up the buoys until the Claymore was held tight in the middle of the web of mooring blocks. By releasing or tightening certain cables, the position of the salvage ship could be adjusted a few feet in any direction.

The next task was to blast a way into the ship. To do this, the crew stuffed guncotton into waterpipes, and sealed the ends. Insulated electrical wires were fed inside the waterpipes.

One of the Johnstone brothers would get into the diving chamber and be lowered to the wreck. Then the waterpipes containing the explosives, were lowered. Watching out the porthole, one of the Johnstones would instruct the crew above, to move the explosives until the waterpipes were laying in the correct position on the side of the ship. Once they were in place, the observation chamber would be lifted out of the water, and an electrical charge would detonate the explosive.

When the water had settled, the chamber would be lowered to the grab again, but this time a large steel grab would be lowered alongside it. The diver in the chamber would direct the crew above to tear twisted metal from the side of the wreck.

The work was slow and frustrating, especially as the crew had to work throughout winter, when constant storms forced them to run for shelter in Whangarei Harbour.

But very slowly, over the coming months, a way was cleared toward the bullion room door.

TO BE CONTINUED